Archives

-

Digital Empowerment: Transforming Community Growth, Health, Economic Development, and Conservation through Innovative Technologies

Vol. 25 (2024)Dear Reader,

The Social Innovations Journal (SIJ) set itself apart from traditional academic journals by being a journal written by and for practitioners. The journal was inspired by two Eisenhower Fellows who realized there needed to be a publication where practitioners could tell their stories and more importantly, share their social sector models for adoption and implementation in other ecosystems. To meet traditional academic standards, SIJ has adapted to become peer reviewed and is in the process to be indexed. However, SIJ will remain committed to practitioners and changemakers who promote innovative ideas, incubate social innovations, and spark a culture of innovation.

SIJ is proud to bring you this edition titled, 'Digital Empowerment: Transforming Community Growth, Health, Economic Development, and Conservation through Innovative Technologies.' This edition was curated by Atmashakti Trust who, in order to bring you these narratives, asked changemakers across the globe to articulate their stories. This edition provides you access to the stories of real people, real challenges, and real triumphs reflecting the resilience, creativity, and dedication of individuals and communities making meaningful impact.

As we embark on this journey together, we are thrilled to share with you the stories and innovations that have emerged from the very heart of our communities. These narratives are not just about technological advancements or academic achievements—they are about real people.

In curating this publication, we faced the challenge of reaching out to practitioners and grassroots organizations deeply immersed in their vital work. We understood the difficulty of asking busy individuals to step away from their endeavors to articulate their stories. Moreover, there is often a perception that academic journals are solely for scholarly pursuits, making it daunting for those not familiar with academic writing standards. However, we saw an opportunity to bridge this gap by embracing the authenticity and richness of their experiences.

Atmashakti Trust’s expertise in the field helped navigate these complexities with empathy and insight. We worked tirelessly to encourage and support practitioners in crafting their narratives, ensuring their voices were heard and their achievements celebrated. This approach not only honours their work but also enriches our understanding of how digital tools, health interventions, socio-economic initiatives, and conservation efforts are reshaping our communities.

Each narrative in this publication—from empowering village voices through digital platforms to leveraging technology for grassroots empowerment and sustainable development—reflects the resilience, creativity, and dedication of individuals and communities striving to make a meaningful impact. These stories illuminate the pathways to empowerment and inspire us to continue fostering innovation and collaboration.

We invite you to immerse yourself in these narratives, to reflect on the challenges and triumphs shared within these pages, and to join us in celebrating the transformative power of grassroots initiatives. Together, let us embrace the potential of digital empowerment and forge a future where every community thrives.

Ruchi Kashyap Nicholas Torres

Executive Trustee, Atmashaki Trust Co-Founder/Publisher, Social Innovations Journal

-

Innovations in Cross-Sector Collaborations: An Approach to Increase Ecosystem and Place-Based Impact

Vol. 24 (2024)Dear Reader,

The Social Innovations Journal (SIJ) has been and is at the heart of collaborations and social impact for over 15 years. Since 2008, SIJ has brought nonprofits, philanthropy, government, businesses, and civic leaders together to collectively focus their expertise and resources on complex issues of importance.

In response to our readership and community expressing the need for greater coordination and coalition-building among organizations and across sectors, we are publishing this edition titled 'Innovations in Cross-Sector Collaborations: An Approach to Increase Ecosystem and Place-Based Impact'. This edition is complimentary to the prior editions curated by the Tamarak Institute titled Community Innovation: A Place-Based Approach to Social Innovation and Transformative Community titled Transformative Partnerships: Proceedings of Transformations.

Strategic collaborations that convene government, philanthropy, private sector, and community result in better 'collective' problem solving to address the core challenges of a region. These spark further innovations and collaborations across sectors based upon collective problem-solving approaches, attract and leverage federal, state, and local investments, drive regional policy change, and build capacity, learning from and with each other, of all sectors through the exploration, project development, and implementation of solutions.

Cross Sector Collaborations need to be based on relationships between organizations, people, and those collaborating around common interests. These relationships are not static, but rather grow and develop as new members continually come to the table. A regional cross-sector network cannot be an insular effort but needs to be an ever-evolving and inclusive network that embraces many types of organizations that strive to create educational practices and community approaches, develop the evidence for what works, and partner on research and action. Cross sector collaborations need to address problems by looking for what is working and why. This accelerates the process of positive change by occupying people with doing rather than dwelling on why it can't be done.

Cross sector collaborations need to lead by returning humanity to communities, including community voices, culture, lived experiences, empathy, and understanding. A cross-sector network needs to work towards improved partnerships and collaborations with regional and national associations and institutions that are aligned in strategies, efforts, and initiatives. The aim is to increase collaboration and inclusion of all participants in the ecosystem of the region to achieve healthy individuals and communities.

The intent of this edition is to inspire collaboration which will result in the creation of better problem-solving strategies addressing the core challenges that a region and communities face.

Sincerely,

Nicholas Torres

Co-Founder/Publisher

-

Social Entrepreneurs Leveraging and Shaping Artificial Intelligence

Vol. 23 (2024)Dear Reader,

While tech executives in Silicon Valley and academics in Ivy League Schools are busy proliferating ethical AI principles and voluntary commitments to manage risks, a key voice is missing from the conversation. Flying under the radar is a growing group of social entrepreneurs leveraging AI for social impact and shaping its trajectory. With ethics at the center of their work, these practitioners constitute an early warning system for the unintended consequences of technology, as well as an innovation engine, constantly building new ways to address both age-old and emerging challenges. There is no more important time than now to pay attention to these bright spots, the lessons they are teaching us about building tech that works for humanity, and the role we can all play. Leading social innovators are vital stakeholders and potential leaders in the journey to build responsible AI (and its accompanying safeguards).

Ashoka and OpenNyAI teamed up for this publication to highlight not just bright spots in our global ecosystems but also the key how-tos that can help more social innovators and responsible AI practitioners move up their learning curves faster.

Presently, the majority of the world’s social entrepreneurs have yet to adopt AI in their work. Whether it is out of concern for the potential negative impacts of these technologies or because of resource constraints, this represents an untapped opportunity on two fronts. Though AI, like any other technology, is just a tool and never a solution in and of itself, it can reveal brand-new opportunities for impact that will not be uncovered unless social entrepreneurs lead the way. In addition, and perhaps even more importantly, if social entrepreneurs remain absent from this space, they will have no chance of significantly shaping the future of AI. We urgently need an on-ramp to learn how to build with AI and simultaneously shape and inform Responsible AI.

In this issue of the Social Innovations Journal, you will find insights on 1) how to build up your organizational readiness and start tinkering responsibly with Artificial Intelligence and 2) practical learnings distilled from use cases in a variety of fields such as justice, health, and media.

Evidently, this is a field that is still in its infancy, but we must begin sharing with each other what works and what doesn’t so we can build what’s next.

Hanae Baruchel, Tech for Humanity Lead at Ashoka

Sachin Malhan, Co-founder at Agami

Nicholas Torres, Co-founder at Social Innovations Journal

________________________________________________

Estimado lector,

Mientras los ejecutivos tecnológicos de Silicon Valley y los académicos de las escuelas de la Ivy League se dedican a proliferar los principios éticos de la IA y los compromisos voluntarios para gestionar los riesgos, hay una voz clave que falta en la conversación. Por debajo del radar hay un grupo creciente de emprendedores sociales que aprovechan la IA para el impacto social y dan forma a su trayectoria. Con la ética en el centro de su trabajo, estos profesionales constituyen un sistema de alerta temprana para las consecuencias imprevistas de la tecnología, así como un motor de innovación, creando constantemente nuevas formas de abordar tanto los retos antiguos como los emergentes. No hay momento más importante que este para prestar atención a estos puntos brillantes, a las lecciones que nos enseñan sobre la creación de tecnología al servicio de la humanidad y al papel que todos podemos desempeñar. Los principales innovadores sociales son partes interesadas vitales y líderes potenciales en el camino hacia la creación de una IA responsable (y las salvaguardias que la acompañan).

Ashoka y OpenNyAI han colaborado en esta publicación para destacar no sólo los puntos brillantes de nuestros ecosistemas globales, sino también las claves que pueden ayudar a más innovadores sociales y profesionales de la IA responsable a avanzar más rápidamente en sus curvas de aprendizaje.

En la actualidad, la mayoría de los emprendedores sociales del mundo aún no han adoptado la IA en su trabajo. Ya sea por preocupación por los posibles efectos negativos de estas tecnologías o por falta de recursos, esto representa una oportunidad sin explotar en dos frentes. Aunque la IA, como cualquier otra tecnología, es sólo una herramienta y nunca una solución en sí misma, puede revelar nuevas oportunidades de impacto que no se descubrirán a menos que los emprendedores sociales lideren el camino. Además, y quizás aún más importante, si los emprendedores sociales permanecen ausentes de este espacio, no tendrán ninguna oportunidad de dar forma de manera significativa al futuro de la IA. Necesitamos urgentemente una rampa de acceso para aprender a construir con IA y, al mismo tiempo, dar forma e informar a la IA responsable.

En este número del Social Innovations Journal encontrará ideas sobre 1) cómo preparar a su organización y empezar a jugar de forma responsable con la Inteligencia Artificial y 2) enseñanzas prácticas extraídas de casos de uso en diversos campos como la justicia, la sanidad y los medios de comunicación.

Evidentemente, se trata de un campo que aún está en pañales, pero debemos empezar a compartir entre nosotros lo que funciona y lo que no para poder construir lo que vendrá después.

Hanae Baruchel, Directora de Tecnología para la Humanidad en Ashoka

Sachin Malhan, cofundador de Agami

Nicholas Torres, cofundador de Social Innovations Journal

-

Transformative Partnerships: Proceedings of Transformations Conference '23

Vol. 22 (2023)Dear Reader,

This edition, titled "Transformative Partnerships: Proceedings of the Transformations Conference ‘23," serves as both a roadmap for action and an invitation to join a collective transformation journey. Curated by the Transformations Community—a worldwide consortium of action researchers and reflective practitioners dedicated to promoting sustainable and regenerative futures—this issue brings together insights from members across various sectors and disciplines. Since its establishment in 2013, the Transformations Community has been at the forefront of fostering transformative thought and action globally. The 2023 conferences, held in Sydney, Prague, Maine, and online, centered on transformative partnerships and featured over 250 sessions. These events attracted over 700 attendees from over 40 countries and included presentations from over 400 distinguished speakers. This special issue, organized around five key themes, captures a rich tapestry of people, ideas, and initiatives from a global community committed to driving transformation towards sustainable and regenerative futures.

Theme 1: Sensemaking and States of the Field: The first article, “Sensemaking the Transformations Community’s Future,” captures ideas and insights from a day-long post-conference gathering in Prague to explore the emerging potential of the Transformations Community. It begins by presenting four principles that unite the Community: Temperance, Transdisciplinarity, Translocalism, and Transformative Learning. These principles are tied to a way forward for the Transformations Community, integrating decentralized conferences, digital resource-sharing platforms, collaborative workspaces, and strategic partnerships to amplify our collective impact. This article is followed by a review of the “State of the Transformations Community,” conducted by former conference organizers as an international hybrid session. The section continues with four "State of the Field" articles, which share ideas about the following domains of professional practice within the transformations field:

- "Network Leadership Development" traces the intricate dance between individual agency and collective impact, reframing leadership as a networked and collaborative process;

- "Systems Education" casts education as a crucible for nurturing empowered, reflective changemakers;

- “Financing Systemic Transformation,” reimagines traditional financial models to align with the complexities of global challenges; and

- "Evaluation and Assessment of Transformation" sheds light on adaptive evaluation methods crucial for deepening our understanding of transformative impacts.

Theme 2: Transformative Partnerships: Six online sessions at the Transformations 2023 Conference are analyzed by participants from each session, each focusing on one of five topics related to the conference’s main theme of “Transformative Partnerships for a Better World”:

- Inner transformation and wellbeing

- Transformative policy and paradigms

- Engaging new narratives for a transformed future

- Transformative leadership

- Transformative policy, institutions, and organizations

The lead article in this section, "Partnerships in Transformations: A Synthesis," interlaces key aspects of the session syntheses that follow, highlighting the fluidity of transformative leadership, the continual journey of transformation, and the vital role of inclusive communities.

Theme 3: Transformative Policies and Practices: Robin Krabbe begins by considering how community basic income in Tasmania addresses social pathology and precarity. Louis Klein and Karima Kadaoui explore metamorphic transformations in social ecosystems, emphasizing the role of humanizing societies through co-reflection. Sarah Velten and her team highlight the importance of multi-level partnerships for biodiversity conservation in agricultural landscapes. Sunny Goddard and colleagues’ research on 'Research Pods' within complementary medicine illustrates a paradigm shift towards more holistic and resilient healthcare methodologies. Bryan Jenkins focuses on the adaptive cycle for ecosystem recovery, and Tani Khara's study on 'Voluntary Simplicity' in urban India offers insights into sustainable dietary practices, emphasizing the transformative role of individual choice. Collectively, these articles underscore how integrated strategies can promote transformations.

Theme 4: Co-producing Transformative Knowledge: Samuel Wearne begins this section by challenging the academic status quo and advocating for knowledge systems that are more plural, contextual, and inclusive. This theme of challenging existing paradigms is echoed in Soli Middleby's work, which critically examines power imbalances in development practices, advocating for a shift towards more equitable and transformative approaches. The concept of relational transdisciplinarity, proposed by Farina L. Tolksdorf and colleagues, further underscores the necessity of collaborative, reciprocal learning processes in sustainability research. Similarly, Lily van Eeden and colleagues utilize a participatory future visioning approach and the Appreciative Inquiry methodology, emphasizing the development of reciprocal relationships with nature to co-produce transformative knowledge for enhancing nature conservation policies and practices. Additionally, Luea Ritter and the team's insights from the World Ethic Forum highlight the importance of inclusive and transformative learning processes rooted in an ecocentric worldview. These papers provide a mosaic of transformative ideas and strategies centered on learning and knowledge practices.

Theme 5: Transdisciplinary Collaborative Design: Justus Wachs and Luea Ritter begin this section by delving into immersive practices for understanding and embodying systemic dynamics, highlighting the creation of spaces for deep relational engagement. Felix Beyers and colleagues discuss the intricacies of shaping transdisciplinary spaces, focusing on the reflective processes essential for navigating complex stakeholder relationships. Roxanne Henwood and colleagues examine the creation of equitable and collaborative spaces in the context of indigenous and colonizing histories. Sydney Hay and colleagues offer insights into the design of participatory labs for bioregional stewardship. Lastly, Rita Golstein-Galperin and colleagues assess the evolving landscape of academic institutions as spaces for transformative innovation. Together, these sessions underscore the significance of carefully designed collaborative spaces and processes in driving systems change.

We hope you enjoy this special issue, which highlights the creativity and vigor of the Transformations Community. We invite you to check out our previous special issues (here and here), subscribe to our newsletter, and join us as we develop new leadership practices, institutional arrangements, and participatory techniques to bring desirable transformations to life.

Thanks to Community Weavers Nick Graham, Thomas Haselbock, Monta Martinsone, and Chukwuma Paul, who made the conferences possible, our Associate Editors, and Shane Casey, a graduate student in the Masters of the Environment Program at the University of Colorado Boulder, who coordinated production of this special issue.

Sincerely,

Bruce Evan Goldstein, Guest Editor and Curator, University of Colorado Boulder

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder and Publisher, Social Innovations Journal

Acknowledgments: A special thanks to the Associate Editors of this edition who managed the process of providing each submission to the special issue with two peer reviews:

Felix Beyers - Research Institute for Sustainability

Anja Bless - University of Technology Sydney

Andrew Gaines - Inspiring Transition

Rita Golstein - Israel Democracy Institute

Flavia Guerra - United Nations University

Adam Hejnowicz - Newcastle University

Johan Holmén - Chalmers

Anne Leitch - Griffith University

Gilles Marciniak - Future Earth

Robson Mukwambo - Rhodes University

Claudia Munera - Environmental Futures at CSIRO

Constance Perrin-Joly - IFSRA, Institute for Social Research in Africa

Glory Dee Romo - University of the Philippines

-

Health Equity: Institutions and Local Ecosystems Responding to People and Society Needs

Vol. 21 (2023)Dear Reader,

We believe that quality equitable health is a human right. We are committed to promoting and implementing Health Equity and understand that to achieve this requires significant change at all levels. We are cognizant of the fact that to achieve Health Equity, we must involve new ways of thinking with governments, institutions, professions, and civil society.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation defines Health Equity where "everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty, discrimination, and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and health care." Achieving health equity requires effective solutions by investing in systems that are designed to improve social and economic conditions, including housing, transportation, education, income and employment assistance, child and family supports, and legal and criminal justice services, and integrating these investments into often disconnected medical and public health programs tasked with improving health.

Our challenge is figuring out “HOW” to shift the aspiration of Health Equity to local action and impact. This edition focuses on three strategies embedded in an anchor strategy. An anchor strategy, first articulated by the Aspen Institute, is a place-based business approach to building community health and wealth by means of local hiring, investing, purchasing, and community engagement. The strategies are:

- Knowledge sharing, learning, and community-based education that serves to motivate individuals to learn and take action. Action is best accomplished by increasing opportunities in which to learn relevant knowledge from diverse colleagues.

- Embracing the assets, successes, initiatives, and evidence about what works within a local ecosystem.

- Supporting Local Change Networks by building upon their capacity through sharing systems and policy change successes and embracing a side-to-side functional model where teaching and learning happen across networks, learning from and with each other.

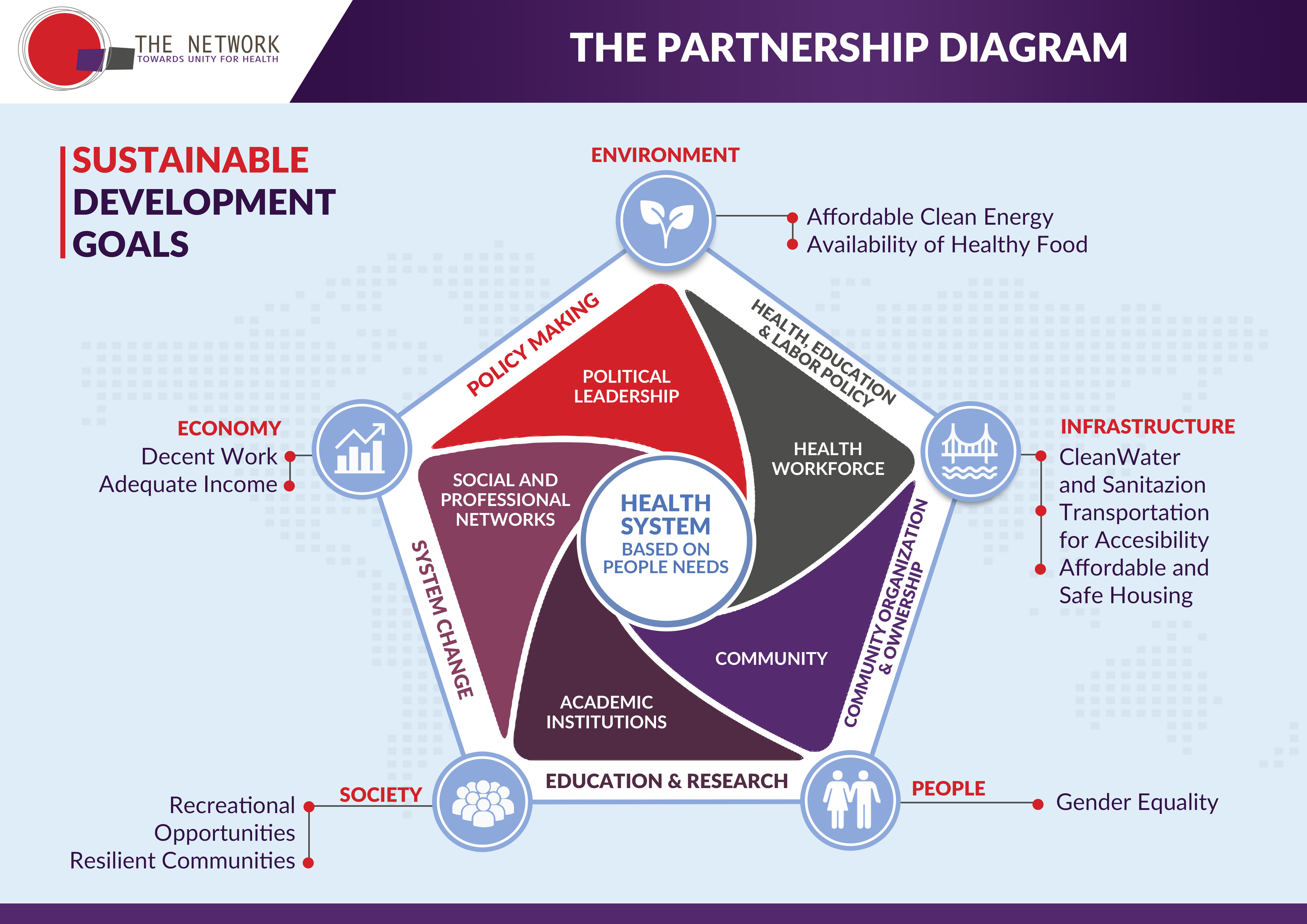

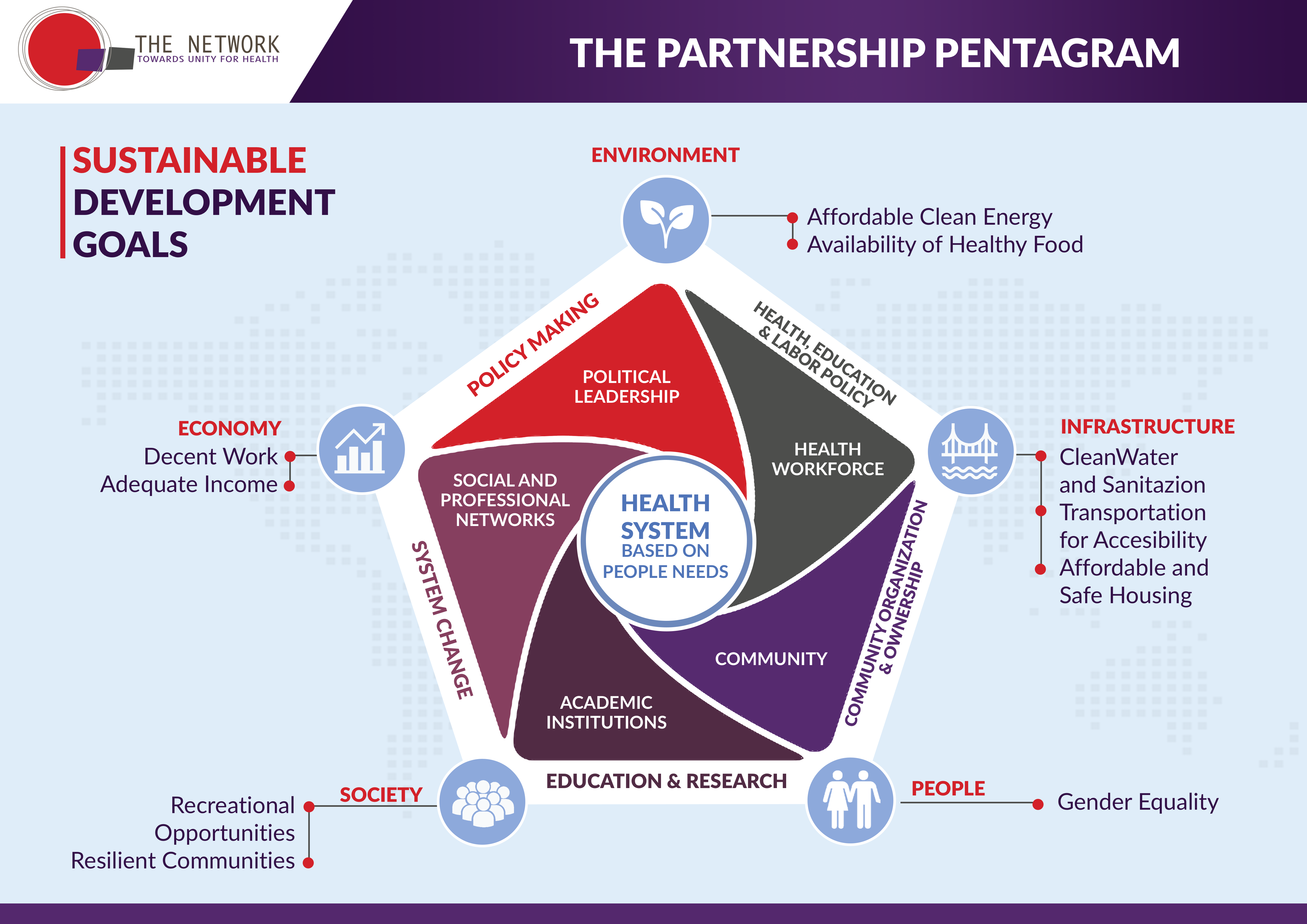

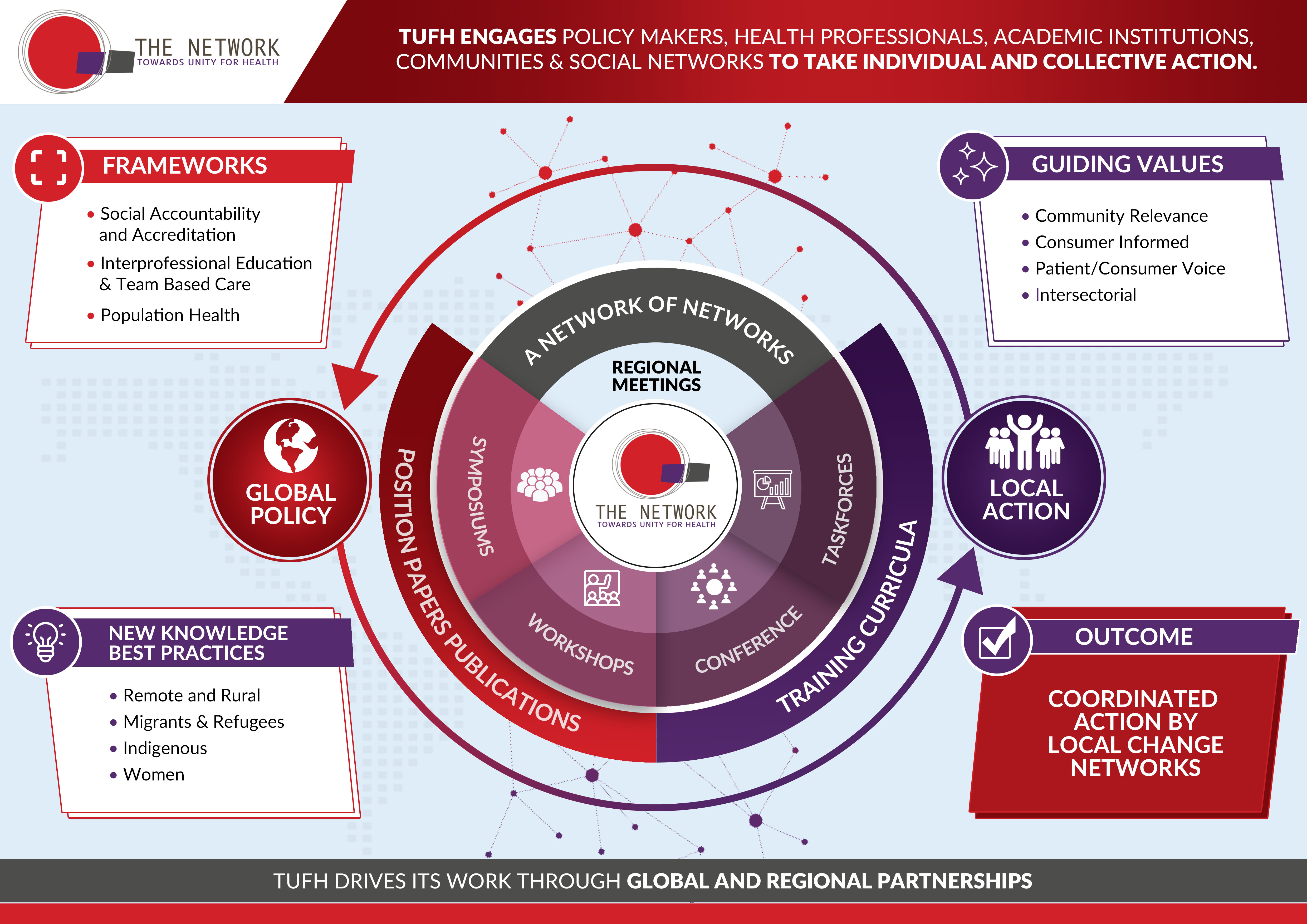

The articles for this edition, a partnership with The Network: Towards Unity for Health and The Alliance for Health Equity, explore many examples of the impact of place-based approaches to achieving Health Equity. The Network: Towards Unity for Health has curated articles focused on the Social Accountability movement in which institutions shift their practices to be responsive to people and society’s needs. The Alliance for Health Equity has curated articles focused on embedding community voice and community-designed solutions and justice and equity into place-based strategies.

Sincerely,

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder and Publisher

Acknowledgements: The art produced for this edition is by emerging artist Ema Navas

-

Population Health Equity for People with Intellectual Disability, Autism, and Mental Health Challenges and Other Special Populations

Vol. 20 (2023)Dear Reader,

For this September 2023 issue, our partner organization, Woods System of Care, has joined us to curate and launch “Population Health Equity for People with Intellectual Disability, Autism, Mental Health Challenges and Other Special Populations.”

Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible while acknowledging that not everyone is the same or requires the same services. Health equity crosses over many sectors, not only disability but also child welfare, criminal and juvenile justice, and aging.

Why is it important to focus on health equity for those with intellectual disabilities, autism, or mental health challenges, and other special populations? Disparities in access to healthcare and health outcomes are significant for those with any disability, especially for the 35% of people with intellectual disability or autism who also have a mental health diagnosis. In the U.S., 1 in 5 people has a mental health diagnosis—that equates to over 43 million people. The need is incredibly great. There are more than 7 million people with an intellectual disability diagnosis in the U.S., and 1 in 36 children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Exacerbating the issue, people who belong to minority groups tend to be diagnosed later and less often. This leads to their missing out on early intervention, which can make an enormous difference in supporting healthy development. Mental health challenges alone—considering that 60% of adults with a mental illness do not receive treatment—have a tremendous impact on a person’s overall health and well-being, which are compounded by other disabilities.

The articles in this issue speak to three broad themes—access to healthcare, inclusion, and promising practices. Just a few of the topics authors address include fostering health equity for Latinx populations with cultural awareness; a 10-step plan for pursuing equity for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and autism and systems change; creating affordable housing for community members with disabilities; a statewide program funding pioneering inclusive, healthy community initiatives for those with disabilities; and using data and technology to enable health equity.

We hope that all stakeholders in this space—individuals receiving services, families, providers, policymakers, and government agencies—will be able to take valuable information from this issue.

Tine Hansen-Turton, Woods Services, Guest Edition Curator and Editor

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal -

Learning from Ecosystems: Gaining Insights Into Equitable and Inclusive Societies

Vol. 19 (2023)Dear Reader,

We strive to live in an equitable society, defined as recognizing that we do not all start from the same place and must acknowledge and make adjustments to imbalances. This edition, 'Learning from Ecosystems: Gaining Insights Into Equitable and Inclusive Societies,' provides insights into ecosystems across the globe and outlines key questions.

The article, 'Building More Just and Equitable Societies Through a Social Innovation Strategy,' identifies social innovation ecosystem principles with the purpose of highlighting legitimate contributors and outlining expected societal impact and improvement returns if the principles are adopted.

Our inspiration for this edition comes from 15 years of publishing the Social Innovations Journal that now has a repository of over 1,250 articles; hosting social innovations awards in Philadelphia, Boston, Chicago, New Jersey, Bogota (Colombia); and hosting social innovation incubator labs for 10+ years. Our Social Innovations work inspires leaders and organizations to continue to dream by creating spaces for social innovators to tap into their own creativity, providing social entrepreneurs with an environment to grow their ideas, challenge social innovators to become better versions of themselves and transform social entrepreneurs and their organizations into changemakers.

This edition, curated by the SIJ team and Michael Wong, provides a look into many ecosystems across the United States and internationally in Africa, the United Kingdom, and Chile. We hope this edition provides you, the reader, with insights into how we might collectively achieve a more just society.

We hope you enjoy reading the articles in this edition and are inspired to lead and drive change within your own ecosystem.

Sincerely,

SIJ Team and Michael Wong

-

Capturing Social Innovation Models by Marginalized Communities from Collective Grassroots Action to Building a Pathway of Systemic Social Change

Vol. 18 (2023)Dear Reader,

We are delighted to share with you the latest edition of our journal, which is dedicated to exploring the power of collective action in advancing social innovation models for sustainable community development.

As you may know, many organizations and collectives are increasingly recognizing the critical role that collective action plays in bringing about inclusive and equitable social change. Atmashakti, a rights-based catalyst organization that coalesces empowerment of Tribal and Dalit communities with a consistent focus on collectivizing the community in Odisha, is a prime example of this approach. Through its work, Atmashakti has shown that no organization or individual can achieve significant social change alone and that a collective approach is pivotal to building a thriving social system that benefits all.

This journal edition highlights the practices, perspectives, and attestations that identify and capture social innovation models, such as the collective actions of the historically marginalized across the country. We aim to showcase how these models empower participants to claim their rights over resources like forests, water, and the environment and to ensure their constitutional, civil, and economic rights. By bringing together all of these elements for broader dissemination and recognition, these models aim at systemic changes that benefit the entire community.

We hope that the stories and insights shared in this journal edition will inspire and inform your work in social innovation and community development. We can build a more just and equitable world through collective action and a people-centric approach.

Thank you for your continued support and readership.

Sincerely,

Ruchi Kashyap, Atmashakti Trust

Nicholas Torres, Social Innovations Journal

-

Community Innovation: A Place-Based Approach to Social Innovation

Vol. 17 (2023)Dear Reader,

We believe that communities drive transformational change. The Tamarack Institute is a Canadian charity with a history of advancing social innovation within communities. We were established 20+ years ago with two big goals. The first was to establish a learning centre that would provide research and document real stories, exemplary practice, and effective applications for community change. The second was to apply what we learned to end poverty.These past 20+ years have shown that community change happens when individuals and networks have

the skills, knowledge, and intention to work collectively around a community goal and focus on impact.

This edition, curated by Tamarack, focuses on the evolving understanding and experience of social

innovation and the chance to profile inspiring examples of the ingenuity of communities. It is focused on

community innovation – defined as a dimension of social innovation that is anchored in communities.

We believe that the practice of social and community innovation is essential in order to meaningfully

impact the complex and interconnected issues confronting individuals, communities, and systems

throughout the world today.COMMUNITY INNOVATION | THE APPLICATION OF SOCIAL INNOVATION IN PLACE

It has been said that ingenuity in the face of adversity is something that humans have been doing since

the beginning of time, reminding us that the notion of social innovation in communities is not new. As

dynamic living ecosystems, communities are ideal environments for experimentation and social

innovation.

At Tamarack, we recognize community innovation as one of five essential skillsets - along with

multisector collaboration, community engagement, collective leadership and evaluating impact –

needed to effectively mobilize and successfully achieve community and systems-level change. Our

approach is based on our understanding that these intertwined challenges can ONLY be resolved with

social innovation, which challenges us to think differently about HOW we think about these issues and, in

discovering, prototyping, and spreading novel solutions to address these challenging social issues.

Distinguishing community innovation within the broader practice of Social Innovation explicitly

acknowledges the importance of place and the reality that each community has unique characteristics,

strengths and challenges that must be considered in the development and implementation of

innovation.WHY PLACE BASED COMMUNITY SCALE?

It is easier to rebuild and strengthen connections, trust, and relationships between diverse

people who live in the same geographic area. Community-wide efforts offer immediate and meaningful opportunities for leadership by

persons with lived experience and inclusive approaches. There is a greater chance of addressing integrated economic social and environmental issues in

practical ways at the scale of community. People are typically more willing to commit to long term efforts to make change when it is

“their” community. Place-based efforts allow for greater flexibility, innovation and responses that fit the unique

nature of distinct communities.SOCIAL AND COMMUNITY INNOVATION PRINCIPLES

1. Community Connections: Strengthen connections and collaborations between diverse people,

organizations, and sectors to grow and align our capacity to make a difference.

2. Place Matters: Focus efforts on places where people live.

3. Hope and Optimism: Focus on the possible and our collective potential for making positive

change.

4. Equity and Inclusion: Engage and elevate the voice of those most impacted by issues who have

the greatest insight into possible solutions.

5. Courage and Learning: Ask difficult questions about the systems and structures which hold

people and communities back and engage in peer-to-peer learning to build our capacity.

6. Action and Impact: Emphasize action and focus on impact.The articles curated for this edition of the journal explore many examples of the impact of place-based

approaches to social innovation focusing on four considerations:1. Tamarack's role in advancing social innovation from a community or place-based lens

(community innovation)

2. How each article is advancing the approach of communities as learning labs

3. How each presented “solution” is distinct from what similar organizations offer and why the

model is successful

4. Case studies and examples to illustrate the "solution"Our conversations do not exist in a bubble and are important parts of larger, intersecting global

conversations and discourses. We welcome readers into these conversations and hope that the articles

in this issue provide insight, share knowledge, and enhance conditions for deeper collaboration among

communities across the globe.Sincerely,

Sonja Miokovic, Tamarack Institute for Community Engagement, Consulting Director, Community

InnovationNicholas Torres, Co-Founder Social Innovations Journal

-

Identifying and Addressing Cultural, Geopolitical, Structural, and Educational Barriers to Social Innovation

Vol. 16 No. 1 (2023)Dear Reader,

Much of current social innovation and changemaking practice occurs within and reflects asymmetries of power, privilege, and knowledge paradigms along cultural, social, and geopolitical lines. This issue explores cultural and geopolitical trends underpinning social innovation, implications for practice, and how changemaking paradigms can make space for knowledge systems within histories of colonization, imperial dominance, oppression, protracted conflict, and the environmental crisis. As the authors in this edition note, for social innovation and changemaking efforts to be successful, we must consider these various knowledge systems and address asymmetrical power structures.

While identifying these barriers, we must also create solutions and methods to overcome these barriers. The articles within this issue highlight research and practices around the world that are working to identify and overcome many of the barriers to social innovation found in asymmetrical power dynamics.

Education, as a key pillar of society, may provide solutions or exacerbate issues depending on how social innovation or changemaking is integrated (or not) into curriculum, leadership, institutional structures, and research agendas. The majority of the articles in this issue address this in some way. All of the articles in this issue were developed in response to Ashoka U’s Third Annual Changemaker Education Research Forum (CERF) held in September 2022. The Forum brought together practitioners and scholars from around the world interested in different aspects of social innovation and changemaking. The Forum was designed to broaden the knowledge base of social innovation and changemaking. In a world where the only constant is change, the Forum and now this special issue of the Social Innovations Journal (SIJ) have focused on creating the conditions for deeper collaboration and knowledge-sharing amongst the changemaker network and beyond, tapping into insights from scholars, practitioners, higher education staff, and students with different perspectives.

CERF 2022 focused on two themes: Cultural, Geopolitical, and Structural Barriers to Social Innovation and the Impact of Changemaker (Social Innovation) Education. A summary of each theme is presented within this special issue of SIJ. Integrated across both themes were issues pertaining to the intersection of education and asymmetrical power structures. This special issue is organized around these four interconnected areas of inquiry:

· International Development

· Local vs. Global

· Responsible Knowledge Creation and Management

· Changemaking in, through, and for Higher Education.

Part one of this edition focuses on international development by looking at specific social issues in Nigeria and Colombia. Part two explores the tensions between 'local' and 'global' approaches and the implications for funding. Part three lays out the various responsibilities of education stakeholders and the importance of careful stewardship of knowledge. Part four is focused on how people have been taking action in, through, and for education to address barriers and find innovative solutions to complex social problems. The research, projects, programs, and case studies shared here highlight issues around asymmetrical power structures and implications for education and provide possible solutions to some of these barriers.

These conversations do not exist in a bubble and are important parts of larger, intersecting global conversations and discourses. We welcome readers into these conversations and hope that the articles in this issue provide insight, share knowledge, and enhance conditions for deeper collaboration among changemakers in all sectors.

Sincerely,

Heather MacCleoud, Ph.D., Chief Network Officer, Ashoka U, Ashoka

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder

Please note with thanks that Ashoka U curated this edition of the Social Innovations Journal

-

Sustainability Transformations in Practice

Vol. 15 (2022)Dear Reader,

Welcome to the Transformations Community’s (TC) second annual special issue, Sustainability Transformations in Practice.

This issue highlights the people, ideas, and initiatives undertaken by TC members that form a global community of action-oriented researchers and reflective practitioners supporting transformations to a sustainable and regenerative future. Our community began in Norway in 2013 with the first Transformations conference, and we have met since then in Sweden, Scotland, Chile, and online during the 2021 pandemic when we released our first special issue. This issue appears in preparation for our sixth international conference in Australia and online in July 2023.

This special issue has four sections. The first section results from a year-long project to understand the transformation community. Over 150 Sustainability graduate students interviewed 56 members of the Transformations Community, asking them:

- How do you pursue transformations in practice, and what skills and capacities do you use?

- What does the word ‘transformations’ mean to you?

- How did you become a transformations practitioner?

- What are your challenges to being an effective transformations practitioner?

A research team led by TC members David Manuel Navarrete, Raksha Balakrishna, and Bruce Goldstein analyzed transcripts from these interviews to produce the four articles in this special issue. Key findings include:

- Transformations practice is rooted in three core transdisciplinary capacities: participatory

diagnosis, expertise in knowledge co-production, and collective action. Moreover, members of our community are 'metadisciplinary', often seeking to advance the transdisciplinary field by developing innovative techniques and integrative leadership practices, creative systems pedagogies, and by reflexive theorizing on their practice. - For practitioners, transformations are a complex, multi-level and multi-phase process that often involves morally grounded commitments to redressing historical injustice. Transformations practice also is often grounded in personal change, which requires re-examining assumptions and core beliefs through disruptive learning experiences.

- As this suggests, becoming a transformations practitioner is often the result of epiphanies and crises that result in abandoning conventional frames and beliefs and turning away from a conventional career path. A practitioner’s meaningful interactions with non-Western cultures often triggered these crises, causing practitioners to “let go” and “unlearn” what counts as valid and useful knowledge and how learning occurs.

- The challenges to being an effective transformations practitioner occur at distinct levels –

personal, professional, and systemic – throughout their transformations journey. Rigidity is a common feature of systems undergoing change and is found within institutions where transformations work occurs, expressed through obstacles such as insufficient financial resources, barriers to collaborative work, and the low priority accorded to action-oriented research.

The next section of this issue highlights three exciting projects the TC has been conducting. The first, by TC staffer Oisin Gill and colleagues, is a deep dive into our Systems Change Education Catalog, which we developed as a resource for students, researchers, and practitioners. The analysis identified three distinguishing characteristics of systems change education programs: audience, pedagogies, and competencies. The second article, by TC staffer Michelle Benedum and colleagues, shares insights from a dialogue session organized by the TC on the ‘Pathways’ Transformative Knowledge Network (TKN), held at the 2022 Sustainability Research and Innovation Congress, a TC partner organization. The last article, by Niko Schäpke and Richard Beecroft, provides guidance on how to monitor and evaluate of highly participatory experimental spaces for transformation, known as “real-world labs”, “living labs” or “transformation labs”. These projects are examples of how the TC supports the spread of innovative techniques, integrative leadership practices, and resources for systems education.

The third section of this issue contains three case studies of efforts to apply the three transdisciplinary capacities of participatory diagnosis, expertise in knowledge co-production, and collective action. The first, by Glenn Page and colleagues, explores how to integrate Indigenous wisdom and western science, confront issues of colonization, and enable collective “seeing” of complex systems through bioregional learning journeys in Casco Bay, Gulf of Maine, USA. The second, by Lee Frankel Goldwater and Abbey Kingdon-Smith, shares lessons for network leadership and practice from a five-year study of the Savory Global Network, a multi-scalar learning network that promotes transformations to regenerative ranching. The last case, by Mary Ann Boyer and Harrison Lundy, is a close look at Philadelphia’s People Advancing Reintegration (PAR) Recycle Works, which pursues social justice and environmental responsibility by coordinating over 200 organizations to collect e-waste, provides transitional employment to people returning from prison, and offers education in digital and financial literacy, conflict management, and mental health strategies.

Our last section contains two excerpts from two influential books that contain core insights for transformations practitioners. A chapter from Peter Plastrik and colleagues’ second book on social innovations networks explores four distinct network leadership roles: Innovation Broker, Network Weaver, Trusted Strategist, and Storyteller. In a chapter from her book on quantum systems change, TC’s founder Karen O’Brien explores how our intentions, assumptions, and values influence our agency and capacity to engage with systems change. O’Brien focuses attention on our continuous “intra- actions” within one entangled system and underscores the importance of actions based on values that apply to the whole, such as equity, dignity, and compassion.

We hope you enjoy this special issue highlighting the creativity and vigor of transformations practice. We invite you to join the TC as we develop new leadership practices, institutional arrangements, and participatory techniques to bring desirable transformations to life. Special thanks to the organizing genius of Nick Graham, the Transformations Community network weaver, our amazing intern Chukwuma Paul, and Shane Casey, a graduate student in the Masters of the Environment Program at the University of Colorado Boulder, who coordinated the production of this issue.

Sincerely,

Bruce Evan Goldstein, University of Colorado BoulderNicholas Torres, Social Innovations Journal

-

Working Title: Institutional Strategies to improve Impact on People's Health: Health Workforce Education and Train in Context and Community Engagement

Vol. 14 (2022)Dear Reader,

Living with Global Health Equity requires that everyone holds a fair and just opportunity to live healthily. To live healthily, we first need to address obstacles to access, such as poverty, poor quality education, housing stability, safe environments, technology, and transportation. Furthermore, we must integrate them into medical and public health programs and regions that are often isolated from growth and innovation. Additionally, we also need to grow the availability of integrated healthcare teams where medical professionals from different fields collaborate with those community workers who have lesser healthcare training but still perform essential tasks and activities.

To achieve global Health Equity, we need:

1) Our higher education institutions to be driven by socially responsible standards. These will help them prepare a workforce that responds effectively to society's and people’s needs. Social accountability and responsibility become an emerging contemporary issue in medical and health professionals' education.

2) To learn with and from each across countries and institutions. Meeting current and future health needs of society and people requires that healthcare workers have the skills that cover all sectors including social, environmental, and technical content in addition to stronger interpersonal and leadership skills. A disciplined approach to continuous improvement will help drive change.

We can measure our progress toward global Health Equity by putting systems in place to measure our impact on society. We need to measure and track our impact on policies, practice, and performance of the health system in the communities we serve. Studying accurate impact ensures that we are addressing society's evolving needs regardless of the political and economical state in the region. This also helps healthcare professionals prepare for situations such as a pandemic, one which brings with it an increased risk to certain minorities, including violence, disparity, racism, and more. Assessing the effect of our work on health systems and society is clearly challenging as it is often influenced by a multitude of complexly interlinked and dynamic factors, many of which are not within the control of our respective institutions.

This edition, written by “pracademics”, focuses on research that has worked toward the reduction of healthcare inequities and improvement of the impact on people’s health. Parts of it shed a spotlight on intimate partner violence statistics during the COVID-19 pandemic, innovation in authentic learning through the use of moulages, and the impact of social responsiveness on empathy, community, and healthy partnership.

Sincerely,

Nicholas Torres and Aricia De Kempeneer

Executive Director and Programming Director

-

Disrupting a Broken System: What the Future Could Look Like for People with Complex Needs

Vol. 13 (2022)Dear Reader,

We are pleased to announce that Woods Services, our partner organization, has joined us to curate and launch our May 2022 edition, “Disrupting a Broken System: What the Future Could Look Like for People with Complex Needs”.

People with complex medical and behavioral healthcare-needs face challenges in accessing services that are integrated and coordinated. Integration of services and systems needs to be improved in order to meet the unique needs of individuals with intellectual disability and mental health issues.

We find solutions first by asking questions. Challenging ourselves with hard quesitons opens our minds to identifying barriers, but more importantly, helps start the journey to finding solutions and innovations. The five essential questions we asked ourselves for this edition include:

1) How can we learn from the past and improve on best practices?

2) What could the future look like if we had model programs and best practices for integrated care that were fully-funded, or if we could widely replicate those models?

3) What could the future look like if we brought together payment systems, workforce systems, global human services, child welfare, and criminal justice systems with the services and systems that support individuals all along a continuum and across these aforementioned silos?

4) What happens when we abruptly close an institution or discontinue funding a particular service model with no viable replacement at hand?

5) What if we knew more about the stories of those who have experienced both the benefits of model programs and the tragic consequences of systemic failure, to better inform the work that we do in the health and human services sector?

The articles in this edition are grouped under four sub-themes:

1) Complex Medical and Behavioral Needs Models and Impact of COVID

2) Global Human Services and Child Welfare Challenges

3) Education Models

4) Workforce Challenges and Innovations

This edition of the Social Innovations Journal responds to the questions posed above, highlighting themes, trends and innovative approaches to improving systems and services in the broad mental health, human services, and intellectual disability sectors which affect all stakeholders – individuals receiving services, families, providers, policy-makers and government agencies. We invite you to explore a range of articles, case studies, policy recommendations, innovative approaches and solutions, and testimonials by families who have experienced the best and worst of the systems and policies in place now.

Sincerely,

Tine Hansen-Turton, Woods Services, Guest Edition Curator and Editor

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal

-

Innovative and Entrepreneurial Nonprofits and Service Models

Vol. 12 (2022)Dear Reader,

Imagine a world where social responsibility standards, transparency, and accountability were the norm. Imagine, if the places we lived in responded to the needs of residents, and the values of equity and justice drove our policies and systems.

The success of the social sector depends on us embracing both tried-and-true traditional practices while simultaneously stepping out of the box to grow new ideas into innovative practices. To achieve a more just society, we need to shift our recognition processes and structures from traditional small societal circles to the public to nominate, acknowledge, and promote organic changemaker leadership who stands to re-envision social sector solutions. These community changemakers serve as catalysts to reshape communities through their innovative ideas, programs, and policies with the potential to disrupt the political landscape and revolutionize our realities; bringing us forward to a more equitable and inclusive tomorrow, today.

Through a public process to nominate, recognize, and promote our most passionate social innovators, entrepreneurs, and changemakers, whose work and social impact too often goes unacknowledged, we start the process of shifting our strategies and investments into the efforts that encourage regions of innovation to thrive and create equitable opportunities for all people.

The primary challenge regions face is the process of finding those social innovators, entrepreneurs, and changemakers because they are too busy promoting their work. The simple solution to the challenge is to open up the nomination, recognition, and promotion process to the public. The Social Innovations Journal has tested and piloted this idea since 2013, resulting in the discovery of 60-75% ecosystem changemakers who were previously unknown to a region’s social sector investors. These previously unrecognized changemakers have introduced innovative solutions with a concrete impact on a region’s people. The process has also resulted in the identification of the primary social sector categories to drive change and inspire vibrant ecosystems. The public nominations, recognition, and promotion of key social sector categories are Innovations in Social Sector Investing, Innovations in Equity and Justice (i.e., community innovations, innovative partnerships, workforce innovations leading to earning a living wage and economic freedom, and education entrepreneurship), and Innovations in Integrated Healthcare Systems with the Social Determinants of Health (i.e., behavioral health, housing, healthy food access).

This issue titled Innovative and Entrepreneurial Nonprofits and Service Models highlights samples of our most passionate social innovators, entrepreneurs, and changemakers. The articles within the edition paint a picture of how a city’s ecosystem can be transformed simply by putting processes in place to find, recognize, and celebrate an ecosystem’s most passionate social innovators, entrepreneurs, and changemakers. By putting the decision in the public’s power through nominations and voting, we amplify the voice of the community, educating government, philanthropic investors, and private social impact investors who are spending more time creating social impact and less time trying to meet the perceived interests of funders.

We hope that this edition serves as a catalyst for cities across the globe to adopt a public nomination, recognition, and promotion process that incentivizes and embraces innovating from the bottom-up by embracing and adopting community solutions. This edition was inspired by a joint effort with NOTLEY and PHILANTHROPITCH, organizations that share a vision to expand the bottom-up model as a new approach to solve our ecosystem's continual challenges of diversity, equity, and inclusion. Their work impacts education, the workforce, economic development, and the social determinants of health.

Notley’s strategy is to team up with a diverse range of passionate people and partners within a city’s ecosystem to combat issues across multiple cause areas with the most effective model possible. Notley’s for-profit/nonprofit approach helps them identify solutions quicker and make the most impact possible. They are on a mission to redefine how these sectors intersect and collaborate with the communities they serve to transform with new models never before thought possible. Philanthropitch was founded as a way to support innovative & entrepreneurial nonprofits and operates in four cities annually: Austin, San Antonio, Columbus, and Philadelphia.

The Social Innovations Journal’s strategy is to host a publicly nominated and voted ecosystem awards process and ceremony that identifies an ecosystem’s most passionate social innovators, entrepreneurs, and changemakers whose work and the social impact often go unacknowledged. This is typically the case while their efforts are what makes their communities the thriving regions of innovation and opportunity they are. The strategy promotes a culture of bold thinking and problem-solving, increasing awareness and building a culture for social innovation, and increasing Social Impact investments by Social Sector Funders and Investors to an ecosystems changemakers.

We would like to congratulate all the authors who wrote for this edition, who are not only making a tremendous impact on their communities but are putting in the extra time to share their impact and models with other social innovators, entrepreneurs, and changemakers across the globe.

Sincerely,

Nicholas Torres Georgia Thompson Katie Hall

Co-Founder/CEO Chief Programs Officer Executive Director

SIJ Notley Philanthropitch

-

Global Trends in Social Entrepreneurship: Developments in a COVID-19 World

Vol. 11 (2022)Dear Reader,

In achieving the Social Innovations mission we again have partnered with Ashoka to bring you the latest trends in social entrepreneurship globally. The Social Innovations Journal is dedicated to social innovators and entrepreneurs who work at the cross-section between the private sector, government, and not-for-profits and aligns them toward collective social impact and public policy goals.

In 2018 Ashoka partnered with the Social Innovations Journal to curate a whole issue on the latest trends in the field of Social Entrepreneurship. The issue, titled "From Social Entrepreneurship to Everyone a Changemaker – 40 Years of Social Innovation”, was based on evidence which had emerged from a study open to all Ashoka Fellows, comprised of quantitative and qualitative data.

Three years later, a pandemic has brought the whole world, perhaps for the first time in history, to experience the same social problem practically at the same time. The severity, scale and simultaneity of the challenge was unprecedented, and it shook the field of social entrepreneurship, much like every other field.

"Everyone a Changemaker”, the belief that empathy and changemaking are the building blocks for a society where solutions outrun problems, has had a global stress-test. Some social entrepreneurs saw their sources of income collapsed, some others an unparalleled opportunity to grow their impact. The use of technology leapt almost overnight. Its potential to aide human development became clearer, as well as the difference in access to technology became more visible and acute. The potential threat to privacy and democracy also emerged stronger.

In response, Ashoka, the largest network in the world of social entrepreneurs and changemakers, decided to run another study among its Fellows, to take stock of what is happening in the field considering these pressing developments. In April 2021, Ashoka launched its Ashoka Fellows Study, comprised of a survey that went out to all fellows and was completed by over 800 social entrepreneurs, from 80 different countries. The study was run in partnership with Tiresia, the Business School of the Polytechnic of Milan, Italy. In May and June 2021, in-depth interviews were carried out with 32 randomly selected social entrepreneurs representing different geographies, fields of work, genders and years of activity.

This edition of the Social Innovations Journal titled: "Global Trends in Social Entrepreneurship: Developments in a COVID-19 World" presents the results and insights based on the study. Insights include implications relevant to business sector, tech, young people, women, DEI as well as social entrepreneurs and those who support them. We encourage you to read all the articles in the journal as outlined below.

We would like to thank all those who made the 2021Ashoka Impact Study, and this follow-up journal volume, possible: Diana Wells and Alexandra Ioan for your leadership; Faith Rotich, Alyssa Matteucci, Somerset Gall and Meghana Parik for your support; Veronica Chiodo, Mario Calderini and their team at the Polytechnic of Milan for their valuable partnership. A special thank you to the fellows for participating in this study with generosity and honesty. Your inspirational leadership guides us at Ashoka, as well as many others around the world.

Sincerely,

Alessandro Valera, Edition Curator and Global Impact & Evidence Team - Europe, Ashoka Italy Founder

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal

-

Transformative Social Innovations: Cross Sector Collaborations and Partnerships

Vol. 10 (2021)Dear Reader,

The pandemic has made it clear that the world is facing increasingly complex challenges. These have manifested in deep social inequalities, high economic instability, and increased fragility of our governance systems across the globe. Additionally, COVID-19 has made more prominent the increasing interdependence of our societies. Thanks to globalization and technological advances, our individual actions can have immediate and wide-reaching effects.

Our current context calls for a new approach to understanding problems and new ways of organizing for transformational change. We tend to think about this from a fragmented perspective. For example, social, environmental, and economic challenges are often seen as separate from one another. This narrow view is reflected in how we address problems—focusing on one issue at a time and through siloed efforts. Yet the complexity of global dynamics means that, to achieve lasting change, we need to engage diverse voices and collectively find solutions for the good of all. Bringing together different perspectives can help to make sense of the full picture, balance potential competing goals or values, and pool knowledge and resources to envision new pathways for creating change.

In recent years we have witnessed the emergence of unique partnerships and cross-sector collaborations that give us insights into the way forward. Social innovators everywhere are providing systemic and effective solutions that challenge current economic and political models. Although these innovations arise from different concerns and perspectives, they share a focus on co-creation across sectors, more systemic approaches that embrace complexity, and deeper and more diverse citizen participation. Moreover, the conceptual cornerstones that unified the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) set a precedent that characterizes and connects cross-sector initiatives. Looking ahead, it will be crucial to accelerate this transition towards a new paradigm that can rise to the challenge of building a more sustainable future.

This edition of the Social Innovations Journal titled Transformative Social Innovations: Cross Sector Collaborations and Partnerships outlines the architecture of transformative social innovations, with a focus on Latin America. The edition makes an in-depth examination of outstanding social innovations that have emerged in response to the exacerbation of socio-environmental challenges. These examples illustrate the key elements that contribute to creating positive social transformation and resilient societies. The analysis also reviews the history of social innovation in the region, facilitating an understanding of the emerging principles that the case studies demonstrate.

We hope this edition will provide inspiration and useful lessons that social innovation leaders can apply to drive transformative solutions within their own ecosystems; create space for reflection on how to engage diverse voices to innovate; and challenge leaders across sectors to break down barriers to foster co-creation.

Yours in Social Innovation

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal

Linda Peia, Ashoka

Vanessa Vargas, Ashoka

Sebastian Gatica, CoLab Innovación Social UC

Special Acknowledgements

Edition Co-editors: Linda Peia, Maria Cerdio

Content Curators: Sebastian Gatica, Linda Peia, Vanessa Vargas

Peer Reviewers: Tasso Azevedo, Hanae Baruchel, Florencia Gay, Alexandra Ioan, Delfina Irazusta, Hector Jorquera, Vincent Lagace, Joaquin Leguia, Maria Luisa Luque, Cristina Monje, Oscar Romo, Luis Antonio Villanueva, Candelaria Yanzi

The Latin America compilation is the result of a joint collaboration between Ashoka and the CoLab of Social Innovation - UC thanks to the support of the PES Latam alliance.

-

Health Equity to improve Impact on People’s Health

Vol. 9 (2021)Dear Reader,

Health Equity requires that “everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be healthier” by “removing obstacles to health such as poverty….. lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality of education and housing, safe environments, and health care.”[1] Achieving health equity requires effective solutions by both investing in systems that are designed to improve social and economic conditions including housing, transportation, education, income and employment assistance, child and family supports, and legal and criminal justice services and integrating these investments into often disconnected medical and public health programs tasked with improving health.

Applying Social Accountability/Responsibility Standards (Student Recruitment, Selection and Support; Faculty Recruitment and Development, Educational Program, Research, and Governance, School Outcomes and Societal Impact) to academic institutions provides a mechanism to connect, collaborate, and integrate services to increase health equity with the ultimate goal of improving the quality of health service delivery for all.

One important Social Accountability Standard is Societal Impact. Societal Impact ensures that programs and schools are addressing evolving needs in the society, regions and communities they serve. Academic institutions need to regularly seek to evaluate the outcome of their efforts as well as the impact they are having on graduates and their practice. Ultimately, they should measure their impact on policies, practice and performance of the health system and health in the communities they serve. Assessing the effect of education strategies on health systems and population health is clearly challenging as it is influenced by a multitude of complex, interlinked, dynamic factors and conditions many of which are not within the control of the education institution. Consequently, researchers need to apply multiple methodologies to build evidence for attribution, contribution, and accountability. Schools striving towards greater accountability and impact are beginning to assess impact.

This edition, written by “pracademics”, focuses on articles in case study and story format that have reduced healthcare inequities and improved the impact on people’s health. Articles in this edition focus on productive partnerships with health actors including policy makers, health professionals, academic institutions, communities and health administrators.

The articles featured in this edition provide a framework that academic institutions and health systems to consider when measuring their societal impact.

[1] Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. From Vision to Action: measures to Mobility a Culture of Health. Princeton: RWJF; 2015.

Nicholas Torres

Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal

-

A Healthcare Workforce Cadre That Meets A Country’s Needs

Vol. 8 (2021)We live in a global healthcare workforce crisis. The World Health Organization’s Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 (”GSHRH”) emphasizes the importance of dynamic and effective health practitioner regulation to the achievement of SDG3: Good Health and Wellbeing. In recent years, regulatory mechanisms and resources across WHO Member States have experienced substantial stress due to the increasing volume and privatization of health professional education, rising importance of previously unregulated occupations; emergence of new occupations; emergencies and humanitarian crisis; accelerating international mobility; new modes and cross border service delivery (e.g. use of digital technology); increasing focus on team-based and integrated networks for service delivery; as well as increasing consumer demand, expectation and knowledge. A synthesis paper was published in February 2015 to inform the beginning of a Global Strategy which is of tremendous value to all relevant stakeholders in the health workforce area, including public and private sector employers, professional associations, education and training institutions, labour unions, bilateral and multilateral development partners, international organizations, and civil society.

Driven by a moral compact to mend the fabric of our communities upon which health depends, The Social Innovations Journal has partnered with The Network: Toward Unity For Health (TUFH), Physician Assistants for Global Health (PAGH), International Academy of PA Educators (IAPAE), International PA Organization (IPAO), Global Association for Clinical Officers (GACOPA), and the International Federation of Physician Assistants/Physician Associates and Clinical Officer/Clinical Associate/Comparable Student Federation (IFPACS), the Beyond Flexner Alliance, and AFREHealth to strengthen knowledge networks in order to share experience and best practices in health practitioner frameworks and their evolution across countries. We believe that strengthening knowledge networks will lead toward the adoption and implementation of global policy recommendations locally.

The World Health Organization (WHO) in 2008 advocated for “Treat, Train, Retain” which refers to the implementation of task-shifting in attempt to meet the unmet burden of disease. Task shifting/sharing refers to healthcare workers with less training and qualifications performing tasks and activities that meet the country’s needs. There isn’t any set structure on how to implement task shifting; however, there is an abundance of literature describing the need for task-shifting and task sharing. The Beyond Flexner Alliance launched The Health Workforce Diversity Tracker to promote greater racial and ethnic parity in the health workforce through measurement and accountability. The issue of highest concern, in terms of inequalities in healthcare is deepening the diversity of the workforce as an optimal strategy to address racial disparities. But this goal remains elusive without accurate data on the composition of the workforce, the pipeline, and clear benchmarks for organizations to strive toward. The Health Workforce Diversity Tracker is dedicated to addressing under-representation among healthcare workers by analyzing data on the diversity of the health workforce and the educational pipeline across thirty health occupations, from front-line workers to physicians.

Combining the reality of task-shifting within the promotion of racial and ethnic parity in the health workforce, this edition of the Social Innovations Journal titled: A Healthcare Cadre That Meets A Country’s Needs provides practical tools and solutions to support local change networks to address the global health workforce crisis. Included in this edition, to serve as a guide for other healthcare workforce cadres, is a database of articles as a medical anthropological approach by a non-physician clinician for 31 countries for non-physician clinicians. This data has not been previously described in the literature by NPCs themselves and we hope this concentration of country-by-country case studies serves as a window of one workforce cadre to fulfill the healthcare workforce gap.

Mary Showstark, Guest Edition Curator and Editor

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal

-

Economic Inequality, Social Mobility, and Institutionalized Racism

Vol. 7 (2021)Dear Reader,

Income inequality in the United States has steadily worsened since the 1970s.[1] We have experienced a 39% increase in income inequality in under four decades—and it comes as a result of an increase in inequality each decade.[2] Furthermore, with the growth in income inequality in the United States, it is decreasingly plausible that someone born into a lower-income household will achieve a higher income as an adult. A 2012 study by The Pew Charitable Trusts showed that 43% of those born into the bottom fifth of households are stuck there, and with social mobility declining since the 1970s, matters are only worsening.[3]

People from around the world come to the United States for the promise of the “American Dream,” the notion that a person born into the bottom economic rung can rise to the top. The same Pew study showed that just 4% born into the lowest-earning 20% of United States families rise to the top 20%.[4] We need to face the reality that the American Dream is more suitably titled the “American Myth.” Or, in the words of Ta-Nehisi Coates, “The American Dream is a lie.”[5]

The situation only becomes more pressing when we consider how income inequality affects Black, Indigenous, and Hispanic and Latino Americans. While the United States has seen massive strides in civil rights, education, and history-making achievement for Black Americans since 1970, median Black household income as a percentage of white household income has only increased 5%—from 56% to 61%—with Latinx Americans earning only slightly more.[6] In terms of social mobility, things are more challenging for people of color, too. Over half of Black Americans born into the bottom fifth of households remain there as adults, while this number drops to 33% for white Americans.[7] It is also more likely that Black Americans will experience downward mobility than white Americans.[8]

Given the magnitude and enduring nature of these issues, we need more than just solutions. We need innovative solutions that address the underlying institutional, systematic, and societal barriers that collectively—both intentionally and unintentionally—reinforce economic disparities. Articulating these solutions will push us all to think more creatively and act more decisively.

This edition of The Social Innovations Journal will do just that. We aim to provide insight into the problems of income inequality, social mobility, and the role of institutional and social racism. Moreover, we hope to share solutions and shed light on bright spots where organizations and individuals are overcoming society’s limitations. We also will share policy suggestions and case studies, to encourage lobbyists and policymakers to enact broad changes to make it easier for all people in the United States to achieve the dream we have been promised.

April Kaplowitz, Guest Edition Curator and Editor

Nicholas Torres, Co-Founder, Social Innovations Journal

[1] U.S. Census Bureau, “Income and Poverty in the United States,” U.S. Census Bureau, 2018, Table A-4.

[2] Juliana Horowitz, Ruth Igielnik, and Rakesh Kochhar, “Most Americans Say There Is Too Much Economic Inequality in the U.S., but Fewer Than Half Call It a Top Priority,” Pew Research Center, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality.

[3] The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Pursuing the American Dream: Economic Mobility across Generations,” The Pew Charitable Trusts, 2012, https://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/legacy/uploadedfiles/wwwpewtrustsorg/reports/economic_mobility/pursuingamericandreampdf.pdf; Kathrine Bradbury, “Trends in U.S. Family Income Mobility, 1969 – 2006,” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 2011, https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/research-department-working-paper/2011/trends-in-us-family-income-mobility-1969-2006.aspx.

[4] The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Pursuing the American Dream.”

[5] Ta-Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me. (New York City: Spiegel & Grau, 2015), 52.

[6] Kathrine Schaeffer, “6 Facts about Economic Inequality in the U.S.,” Pew Research Center, February 7, 2020, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/02/07/6-facts-about-economic-inequality-in-the-u-s.

[7] The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Pursuing the American Dream.”

[8] The Pew Charitable Trusts, “Pursuing the American Dream.”

-

Innovations in Community-Based and Center Based Services

Vol. 6 (2021)Dear Reader,

Since the advent of key pieces of federal legislation, including the Community Mental Health Act of 1963, the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990, and the Olmstead Decision of 1999, the trend has remained consistent towards locating services in the community and in the home for children and adults with all kinds of disabilities, including mental health challenges, intellectual disabilities, autism, physical disabilities, and others. In the Olmstead Decision, the Supreme Court held that community-based services should be provided to persons with disabilities when (1) such services are appropriate; (2) the affected persons do not oppose community-based treatment; and (3) community-based services can be reasonably accommodated, taking into account the resources available to the public entity and the needs of others who are receiving disability services from the entity.